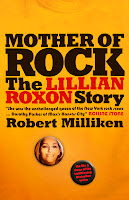

Robert Milliken is the author of Mother of Rock: The Lillian Roxon Story. Mother of Rock is the riveting true story of trailblazing Australian rock journalist Lillian Roxon.

Robert Milliken is the author of Mother of Rock: The Lillian Roxon Story. Mother of Rock is the riveting true story of trailblazing Australian rock journalist Lillian Roxon. Who was Lillian Roxon?

Lillian Roxon was a brilliant Australian journalist who took New York by storm in the 1960s and early 1970s. Her book Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia (1969) was the world’s first encyclopedia of rock music. It still stands as an unparalleled chronicle of the classic names in music and counterculture from that turbulent era. Lillian became a Dorothy Parker figure at Max’s Kansas City, the New York bar and nightclub where the stars of that time gathered. In New York today, she is still recalled as “the mother of rock and roll journalism”.

What drew you to writing about Lillian Roxon?

As a student in Australia, I was a fan of Lillian’s writing about America from New York (she was then a correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald). Whatever the subject – flower children, Andy Warhol, Janis Joplin, Richard Nixon’s 1968 Presidential campaign – she brought it to life with a style that sprang from the page and bucked the rigid writing conventions back then by often putting herself in the story. Then she died tragically from an asthma attack in 1973, aged 41. Years later, I discovered Lillian’s family had lodged her papers with the Mitchell Library in Sydney. She was one of the last great letter writers. Her papers included her correspondence with a who’s who of art and culture in Australia and New York. With many of those figures still available to be interviewed, I decided there was a story to be told about a writer who, in many ways, defined an era.

Why is Lillian such an important Australian identity?

Lillian was one of the great Australian trailblazers. She came to Australia as a child with her Jewish family just before the second world war to escape Hitler and Mussolini. She was a rebellious teenager during the war years in Brisbane, then awash with American servicemen. In Sydney, she was a star figure in the Push, the group of bohemians who questioned the social and sexual mores of 1950s Australia. Donald Horne discovered her as a journalist. She started her working life on Weekend, a lively tabloid he edited for Sir Frank Packer. Lillian was his favourite writer. When she left for America in 1959 – stopping in Hawaii on the way to interview Elvis Presley’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker – he begged her to stay, then offered her all sorts of job inducements to come back, to no avail. And in America, Lillian held on proudly to her Australian identity and accent. Here again, she defied convention: most Australians who moved to America then soon became de facto Americans. She was a great champion of Australian writers, artists and musicians who needed help in New York. On the Australian Ballet’s first big tour of America in 1971, she threw a party for the company at Max’s Kansas City. Lou Reed and Iggy Pop were among her 250 guests.

Thirty-seven years after her death, Lillian’s story seems to keep growing in stature. A documentary, which my book inspired, is due to premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival in July, before screening on SBS. It’s called Mother of Rock: the Life and Times of Lillian Roxon, produced by Robert de Young and directed by Paul Clarke.

And 40 years after the publication of the Rock Encyclopedia, some of the most influential figures in the music business in America still hail its unique contribution. Danny Goldberg, a former music journalist who knew Lillian (he covered the 1969 Woodstock festival for Billboard), and later record company President (Atlantic, Warner Brothers and Mercury), says Lillian had an elevated notion of rock and roll as culture that was ahead of its time. Goldberg, who now owns and operates Gold Village Entertainment, an artist management company, told me:

“Lillian Roxon’s Rock Encyclopedia set the tone for writing about rock and roll for years, with ripple effects that endure to this day. Previously, there were two extremes: breathless fan magazine fluff, and often ponderous intellectual over-think. Lillian was able to bridge the gap and speak in the language of the millions of fans of rock and roll who emerged after the late 1960s. She understood brilliant and sexy were not contradictions, but went together in the best of rock and roll. She was able to express the perspectives of both a teenager and an adult in the same passage, uniquely reflecting the mixture of emotions that existed in rock music, in its fans and in herself.”

Of all the famous stories and anecdotes about Lillian, which is your favourite?

David Malouf told me the best one. He was a shy 18 year-old student from Brisbane visiting Sydney in 1953. Zell Rabin, a mutual friend (another brilliant young journalist, and Lillian’s great love) told David to look Lillian up. He went to her flat in Jamison Street, in the centre of Sydney, where Lillian was holding court with her Push crowd. She handed the nervous young man a book called Sexual Anomalies and Perversions by Magnus Hirschfeld, a 19th century German pioneer sexologist. Then she instructed him: “Read this book and put bits of paper in the places that excite you. We want to know everything about you.” It was a classic case of Lillian, the older, independent, fearless woman, setting out to shock. In later years, David Malouf and Lillian remained great friends.

Can you tell us a little bit about Lillian’s feud with Germaine Greer and her friendship with Linda Eastman (who later became Linda McCartney)?

Germaine was not yet a literary star when she visited New York for the first time in 1968. Mutual Push friends had put her in touch with Lillian, with whom she’d hoped to stay. But Lillian’s tiny Manhattan apartment was swamped with papers, as she rushed to meet her deadline on the Rock Encyclopedia. So she sent Germaine to the Broadway Central, which Germaine years later described to me as “a welfare hotel where people screamed and ran up and down stairs all night”. Germaine was not pleased. Lillian also introduced Germaine to the crowd at Max’s Kansas City. They had a terrible verbal fight there one night, and didn’t speak for a year. Although this was the start of women’s liberation, I think these two strong, brilliant, ambitious Australian women – both seeking to make their marks on the world – in some ways were rivals. And, let’s face it, Lillian had already lived the life of a liberated woman long before Germaine wrote the women’s lib bible, The Female Eunuch, two years after Lillian’s Rock Encyclopedia came out. Germaine nonetheless dedicated her book to Lillian. It was a backhanded dedication, for which Lillian never forgave her.

Lillian met Linda Eastman, then an aspiring photographer, in early 1966 when they were both discovering the New York rock scene. Lillian was a good 10 years older than Linda. She saw in her a talent worth nurturing in an industry dominated by men. The two women formed a close professional alliance with Danny Fields, a rock manager who also held considerable clout in the Max’s Kansas City scene. Lillian became Linda’s confidante, especially after Linda and Paul McCartney got together following their meeting at a Beatles press conference. When Linda married Paul, at the height of “Beatlemania”, she cut off contact with Lillian and her other New York rock friends. Lillian was heartbroken and furious, in equal measure. She got her revenge by writing an unflattering piece about the McCartneys (especially Paul) in her weekly column in the New York Sunday News, read by millions. The two women never met again before Lillian died in 1973.

Linda McCartney agreed to talk to me for the book 25 years later. Just before I arrived in London for the interview, the McCartneys’ office told me they’d had to re-schedule and were going away. I didn’t realise how ill from cancer Linda herself was at the time. She died before a later interview was possible. Her break with Lillian was tragic. I think she regretted it in her later years.

What is your favourite piece of writing by Lillian?

There are two, both in the Appendix of Mother of Rock. The first is an essay called “Will Success Spoil Lillian Roxon?” Lillian wrote it in 1970 for Quadrant, not then the archly conservative journal it is now. It’s a wonderful piece, in which she describes how she came to write the Rock Encyclopedia, but is more an incomparable snapshot of her New York world in the late 1960s.

The second favourite is “The Other Germaine Greer: A Manicured Hand on the Zipper”, from 1971, in Crawdaddy, the first magazine in America devoted to rock and roll criticism. It’s a racy, no-holds-barred take on Germaine and, I suspect, Lillian’s last word in their feud.

For further information on Mother of Rock: The Lillian Roxon Story by Robert Milliken, please visit the Black Inc. website.